USUS FRUCTUS ABUSUS

La Blanche et la Noire

Video Installation

2020 - ongoing

This project consists of several formal, narrative and discursive layers that have been developed since 2019.

Property in Roman Law was defined as the absolute and full enjoyment of an object or corporeal entity.

Usus was the right of the owner to make use of the entity according to its destination or nature, fructus was the right to receive both real fruits (money) or fruits in general, and abusus was the right of disposition based on the power to modify, sell or destroy it, and property was perpetual, absolute and exclusive.

Starting from the concept of ownership a dialogue is raised addressing issues around the spoliation, race and gender. Return what has been plundered and looted, both in terms of objects and identity, is it an urgent, universal and feasible question for everyone?

Ownership, restitution, reparation, recontextualization, .... Who has agency to give, return, adjudicate, rename?

The concept of museum was born more than 300 years ago, when the collections of certain monarchs, kings or emperors were opened to the public, being since then institutions that give identity and define a nation. But if the origin of these spaces is colonialist, History, universal rights and ethics come into conflict.

The question of how to safeguard and exhibit works of art, artefacts and even humans remains that were acquired (or, more often, looted) by Europeans, mainly during the heyday of imperialism between the 18th and mid-20th centuries, is an extremely thorny ethical issue. Major institutions in France, Belgium, Germany, Portugal, Holland, Spain and England have, for the most part, a sordid history of dealing with these issues and, unfortunately, not always with the intention of reviewing and rectifying them in the face of an urgency to "decolonize" museums.

It is evident that the museum as an institution is not and has never been a mere container and neutral or beneficial exhibitor of objects and artefacts. To the dismay of museum boards around the world they have become a key battleground in the struggle for decolonization. It is time for a reckoning that addresses the myriad ways in which museums have been and often continue to be the beneficiaries of Europe's violent expansion and exploitation, responsible for a stereotypical imaginary.

Some of them have been produced thanks to the Ayudas a Creación y Desarrollo 2019 Grant from the Madrid City Council, and the Ayudas para la Investigación, Creación y Producción Artísticas en el Campo de las Artes Visuales Grant from the Ministry of Culture and Sport of Spain, both awarded in the 2020 and 2022 calls respectively.

Property in Roman Law was defined as the absolute and full enjoyment of an object or corporeal entity.

Usus was the right of the owner to make use of the entity according to its destination or nature, fructus was the right to receive both real fruits (money) or fruits in general, and abusus was the right of disposition based on the power to modify, sell or destroy it, and property was perpetual, absolute and exclusive.

Starting from the concept of ownership a dialogue is raised addressing issues around the spoliation, race and gender. Return what has been plundered and looted, both in terms of objects and identity, is it an urgent, universal and feasible question for everyone?

Ownership, restitution, reparation, recontextualization, .... Who has agency to give, return, adjudicate, rename?

The concept of museum was born more than 300 years ago, when the collections of certain monarchs, kings or emperors were opened to the public, being since then institutions that give identity and define a nation. But if the origin of these spaces is colonialist, History, universal rights and ethics come into conflict.

The question of how to safeguard and exhibit works of art, artefacts and even humans remains that were acquired (or, more often, looted) by Europeans, mainly during the heyday of imperialism between the 18th and mid-20th centuries, is an extremely thorny ethical issue. Major institutions in France, Belgium, Germany, Portugal, Holland, Spain and England have, for the most part, a sordid history of dealing with these issues and, unfortunately, not always with the intention of reviewing and rectifying them in the face of an urgency to "decolonize" museums.

It is evident that the museum as an institution is not and has never been a mere container and neutral or beneficial exhibitor of objects and artefacts. To the dismay of museum boards around the world they have become a key battleground in the struggle for decolonization. It is time for a reckoning that addresses the myriad ways in which museums have been and often continue to be the beneficiaries of Europe's violent expansion and exploitation, responsible for a stereotypical imaginary.

Some of them have been produced thanks to the Ayudas a Creación y Desarrollo 2019 Grant from the Madrid City Council, and the Ayudas para la Investigación, Creación y Producción Artísticas en el Campo de las Artes Visuales Grant from the Ministry of Culture and Sport of Spain, both awarded in the 2020 and 2022 calls respectively.

Este proyecto consta de cinco estratos formales, narrativos y discursivos que llevan desarrollándose desde 2019.

La propiedad en el Derecho Romano se definía como el goce absoluto y pleno sobre un objeto o ente corporal.

El usus era el derecho que el titular tenía de hacer uso del ente de acuerdo a su destino o naturaleza, fructus el que se tenía a percibir los frutos, abusus el derecho de disposición basado en la potestad de modificarlo, venderlo o destruirlo. La propiedad era perpetua, absoluta y exclusiva.

A partir del concepto de propiedad se abordan cuestiones en torno al expolio, las narrativas hegemónicas, la raza y el género. Devolver lo que ha sido expoliado y saqueado, tanto en términos de objetos como de identidad, ¿es una cuestión urgente, universal y factible para todos? Restitución, reparación, recontextualización... ¿Quién tiene agencia para dar, devolver, adjudicar, renombrar?

El concepto de museo nació hace más de 300 años, cuando fueron abiertas al público las colecciones de ciertos monarcas, siendo desde entonces instituciones que dan identidad y definen a una nación. Pero si el origen de estos espacios es colonialista, entran en conflicto Historia, derechos y ética. Revisar la relación entre una antropología colonial establecida no como estudio de la cultura, sino de la diferencia, y las colecciones museísticas provenientes de un pasado colonial en su mayor parte expoliador; su historicidad y su historiografía, excusada tras una inquietud de descubrimiento y de expediciones casi siempre con espíritu “salvador”; así como su función ejercida durante décadas de refuerzo del exotismo y de la distinción, intrínsecamente relacionados con los discursos supremacistas.

La cuestión de cómo salvaguardar y exhibir obras de arte, artefactos e incluso restos humanos que fueron adquiridos (o, con mayor frecuencia, saqueados) por europeos, principalmente durante el apogeo del imperialismo, es una cuestión ética y pertinente. Las principales instituciones de Francia, Bélgica, Alemania, Holanda e Inglaterra tienen, en su mayor parte, un historial sórdido en cómo se abordan estas cuestiones, y, desgraciadamente, no siempre con intención de revisión/rectificación, ante un urgencia por la “descolonización” de los museos. España también.

El museo como institución no es ni ha sido nunca un mero poseedor y exhibidor neutral o benéfico de objetos y artefactos. Para consternación de los consejos de administración de los museos de todo el mundo, se han convertido en un campo de batalla fundamental. Es hora de un cálculo que aborde la miríada de maneras en que los museos han sido y, a menudo, siguen siendo los beneficiarios de la expansión y explotación violenta de Europa, responsables de un imaginario estereotipado.

Algunos de estos han sido producidos gracias a las Ayudas a Creación y Desarrollo del Ayuntamiento de Madrid 2019, y las Ayudas para la Investigación, Creación y Producción Artísticas en el Campo de las Artes Visuales del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte tanto en la convocatoria del 2020 como en la del 2022.

La propiedad en el Derecho Romano se definía como el goce absoluto y pleno sobre un objeto o ente corporal.

El usus era el derecho que el titular tenía de hacer uso del ente de acuerdo a su destino o naturaleza, fructus el que se tenía a percibir los frutos, abusus el derecho de disposición basado en la potestad de modificarlo, venderlo o destruirlo. La propiedad era perpetua, absoluta y exclusiva.

A partir del concepto de propiedad se abordan cuestiones en torno al expolio, las narrativas hegemónicas, la raza y el género. Devolver lo que ha sido expoliado y saqueado, tanto en términos de objetos como de identidad, ¿es una cuestión urgente, universal y factible para todos? Restitución, reparación, recontextualización... ¿Quién tiene agencia para dar, devolver, adjudicar, renombrar?

El concepto de museo nació hace más de 300 años, cuando fueron abiertas al público las colecciones de ciertos monarcas, siendo desde entonces instituciones que dan identidad y definen a una nación. Pero si el origen de estos espacios es colonialista, entran en conflicto Historia, derechos y ética. Revisar la relación entre una antropología colonial establecida no como estudio de la cultura, sino de la diferencia, y las colecciones museísticas provenientes de un pasado colonial en su mayor parte expoliador; su historicidad y su historiografía, excusada tras una inquietud de descubrimiento y de expediciones casi siempre con espíritu “salvador”; así como su función ejercida durante décadas de refuerzo del exotismo y de la distinción, intrínsecamente relacionados con los discursos supremacistas.

La cuestión de cómo salvaguardar y exhibir obras de arte, artefactos e incluso restos humanos que fueron adquiridos (o, con mayor frecuencia, saqueados) por europeos, principalmente durante el apogeo del imperialismo, es una cuestión ética y pertinente. Las principales instituciones de Francia, Bélgica, Alemania, Holanda e Inglaterra tienen, en su mayor parte, un historial sórdido en cómo se abordan estas cuestiones, y, desgraciadamente, no siempre con intención de revisión/rectificación, ante un urgencia por la “descolonización” de los museos. España también.

El museo como institución no es ni ha sido nunca un mero poseedor y exhibidor neutral o benéfico de objetos y artefactos. Para consternación de los consejos de administración de los museos de todo el mundo, se han convertido en un campo de batalla fundamental. Es hora de un cálculo que aborde la miríada de maneras en que los museos han sido y, a menudo, siguen siendo los beneficiarios de la expansión y explotación violenta de Europa, responsables de un imaginario estereotipado.

Algunos de estos han sido producidos gracias a las Ayudas a Creación y Desarrollo del Ayuntamiento de Madrid 2019, y las Ayudas para la Investigación, Creación y Producción Artísticas en el Campo de las Artes Visuales del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte tanto en la convocatoria del 2020 como en la del 2022.

Project exhibited at Fotofestiwal, Lagos Photo, Scan Tarragona, Art Geneve, Landskrona Photo, Getxophoto, Galerie 21 Hamburg, Fotografia Europea.

DUETTO O DUETTINO

Video Installation

2022

Dual-channel audiovisual projection where the fundamental questions of the project are reflected: the responsibility of the museums in the construction of a stereotyped imaginary and the urgency for the decolonization of these spaces; as well as the responsibility for the representation of black women in European painting.

It is evident that the museum as an institution is not and has never been a mere container and neutral or beneficial exhibitor of objects and artefacts

To the dismay of museum boards around the world they have become a key battleground in the struggle for decolonization and against white/Euro-American supremacy, as indigenous and formerly colonized peoples strive to recover material pieces of their looted cultural heritage.

The concept of museum was born more than 300 years ago, when the collections of certain monarchs, kings or emperors were opened to the public, being since then institutions that give identity and define a nation. But if the origin of these spaces is colonialist, History, universal rights and ethics come into conflict. A review of the relationship between anthropology and museum collections from a colonial past largely plundering, its historicity and historiography, excused behind a concern for discovery and expeditions almost always with a "saviour" spirit, leads to the conclusion that they have exercised for decades a function of reinforcement of exoticism and distinction, intrinsically related to supremacist discourses.

Return what has been plundered and looted, both in terms of objects and identity, is it an urgent, universal and feasible question for everyone?

It is evident that the museum as an institution is not and has never been a mere container and neutral or beneficial exhibitor of objects and artefacts

To the dismay of museum boards around the world they have become a key battleground in the struggle for decolonization and against white/Euro-American supremacy, as indigenous and formerly colonized peoples strive to recover material pieces of their looted cultural heritage.

The concept of museum was born more than 300 years ago, when the collections of certain monarchs, kings or emperors were opened to the public, being since then institutions that give identity and define a nation. But if the origin of these spaces is colonialist, History, universal rights and ethics come into conflict. A review of the relationship between anthropology and museum collections from a colonial past largely plundering, its historicity and historiography, excused behind a concern for discovery and expeditions almost always with a "saviour" spirit, leads to the conclusion that they have exercised for decades a function of reinforcement of exoticism and distinction, intrinsically related to supremacist discourses.

Return what has been plundered and looted, both in terms of objects and identity, is it an urgent, universal and feasible question for everyone?

Proyección audiovisual de doble canal donde se reflexiona sobre las cuestiones fundamentales del proyecto: la responsabilidad de los museos en la construcción de un imaginario estereotipado y la urgencia por la descolonización de estos espacios; así como también la responsabilidad de la representación de la mujer negra en la pintura europea.

El museo como institución no es ni ha sido nunca un mero poseedor y exhibidor neutral de objetos y artefactos.

Se ha convertido en un campo de batalla fundamental en la lucha por la descolonización y contra la supremacía blanca euro-estadounidense, a medida que los pueblos indígenas y los antiguos colonizados se esfuerzan por recuperar piezas materiales de su patrimonio cultural saqueado. La propiedad en el Derecho Romano se definía como el goce absoluto y pleno sobre un objeto o ente corporal.

El concepto de museo nació hace más de 300 años, cuando fueron abiertas al público las colecciones de ciertos monarcas, siendo desde entonces instituciones que dan identidad y definen a una nación. Pero si el origen de estos espacios es colonialista, entran en conflicto Historia, derechos y ética. Es pertinente revisar la relación entre una antropología colonial establecida no como estudio de la cultura, sino de la diferencia, y las colecciones museísticas provenientes de un pasado colonial en su mayor parte expoliador; su historicidad y su historiografía, excusada tras una inquietud de descubrimiento y de expediciones casi siempre con espíritu “salvador”; así como su función ejercida durante décadas de refuerzo del exotismo y de la distinción, intrínsecamente relacionados con los discursos supremacistas.

Devolver lo que ha sido expoliado y saqueado, tanto en términos de objetos como de identidad, ¿es una cuestión urgente, universal y factible para todos?

El museo como institución no es ni ha sido nunca un mero poseedor y exhibidor neutral de objetos y artefactos.

Se ha convertido en un campo de batalla fundamental en la lucha por la descolonización y contra la supremacía blanca euro-estadounidense, a medida que los pueblos indígenas y los antiguos colonizados se esfuerzan por recuperar piezas materiales de su patrimonio cultural saqueado. La propiedad en el Derecho Romano se definía como el goce absoluto y pleno sobre un objeto o ente corporal.

El concepto de museo nació hace más de 300 años, cuando fueron abiertas al público las colecciones de ciertos monarcas, siendo desde entonces instituciones que dan identidad y definen a una nación. Pero si el origen de estos espacios es colonialista, entran en conflicto Historia, derechos y ética. Es pertinente revisar la relación entre una antropología colonial establecida no como estudio de la cultura, sino de la diferencia, y las colecciones museísticas provenientes de un pasado colonial en su mayor parte expoliador; su historicidad y su historiografía, excusada tras una inquietud de descubrimiento y de expediciones casi siempre con espíritu “salvador”; así como su función ejercida durante décadas de refuerzo del exotismo y de la distinción, intrínsecamente relacionados con los discursos supremacistas.

Devolver lo que ha sido expoliado y saqueado, tanto en términos de objetos como de identidad, ¿es una cuestión urgente, universal y factible para todos?

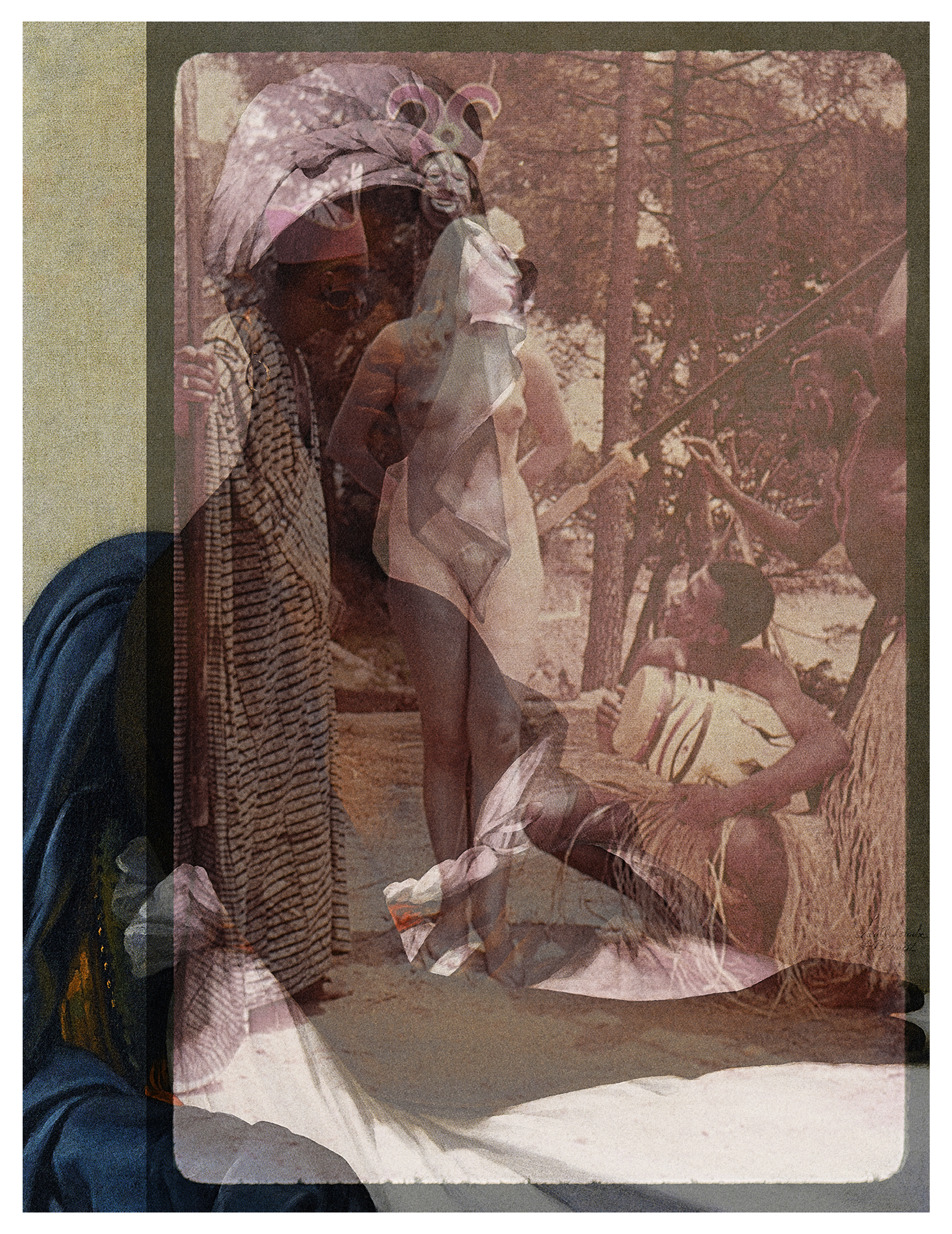

USUS FRUCTUS ABUSUS

Installation

2022

An installation of 7 photographs in the form of diptychs on the one hand printed in large size and framed, on the other printed in large format on fine, fluid voilé fabric. These overlays dialogue between them and reinforce the discourse of the piece Duetto o Duettino. printed in large format on fluid, thin and semitransparent fabric, mounted

The diptychs are mounted on a modular structure made to measure as an articulated screen. They are hung facing each other on the back, creating superimpositions against the light, giving each diptych another narrative layer.

Structure 2 is made of iron with a round profile and fluctuates in space in an undulating circular manner, with an approximate diameter of 4 meters.

Lastly, structure 3 has a round profile and fluctuates in space longitudinally in an undulating manner, with an approximate length of 4 meters.

These last two are in development phase.

Project produced thanks to the Ayudas a Creación y Desarrollo 2019 Grant from the Madrid City Council.

The diptychs are mounted on a modular structure made to measure as an articulated screen. They are hung facing each other on the back, creating superimpositions against the light, giving each diptych another narrative layer.

Structure 2 is made of iron with a round profile and fluctuates in space in an undulating circular manner, with an approximate diameter of 4 meters.

Lastly, structure 3 has a round profile and fluctuates in space longitudinally in an undulating manner, with an approximate length of 4 meters.

These last two are in development phase.

Project produced thanks to the Ayudas a Creación y Desarrollo 2019 Grant from the Madrid City Council.

Instalación fotográfica de 7 dípticos de imágenes impresas en gran formato sobre fino tejido voilé realizadas en ambos rodajes de las piezas de vídeo de Duetto o Duettino que mediante superposiciones dialogan y refuerzan el discurso de la obra.

Los dípticos están suspendidos sobre unas estructuras metálicas de diversos módulos, diseñadas para que la experiencia del espectador sea envolvente y la superposición visual de la obra sea efectiva.

La estructura 1 está construida de hierro creando un biombo de 7 hojas todas de 1 metro de ancho y de 3 alturas distintas (1.40, 1.80 y 2.20 mts), resultando de un largo aproximado de 5 mts.

La estructura soporte 2 es de hierro con perfil redondo y fluctúa en el espacio de forma circular ondulante, con un diámetro aproximado de 4mts.

Por último, la estructura 3 cuenta con perfil redondo y fluctúa en el espacio longitudinalmente de forma ondulante, con una longitud aproximada de 4mts.

Estas dos últimas están en vía de desarrollo.

Proyecto producido gracias a las Ayudas a Creación y Desarrollo del Ayuntamiento de Madrid 2019.

Los dípticos están suspendidos sobre unas estructuras metálicas de diversos módulos, diseñadas para que la experiencia del espectador sea envolvente y la superposición visual de la obra sea efectiva.

La estructura 1 está construida de hierro creando un biombo de 7 hojas todas de 1 metro de ancho y de 3 alturas distintas (1.40, 1.80 y 2.20 mts), resultando de un largo aproximado de 5 mts.

La estructura soporte 2 es de hierro con perfil redondo y fluctúa en el espacio de forma circular ondulante, con un diámetro aproximado de 4mts.

Por último, la estructura 3 cuenta con perfil redondo y fluctúa en el espacio longitudinalmente de forma ondulante, con una longitud aproximada de 4mts.

Estas dos últimas están en vía de desarrollo.

Proyecto producido gracias a las Ayudas a Creación y Desarrollo del Ayuntamiento de Madrid 2019.

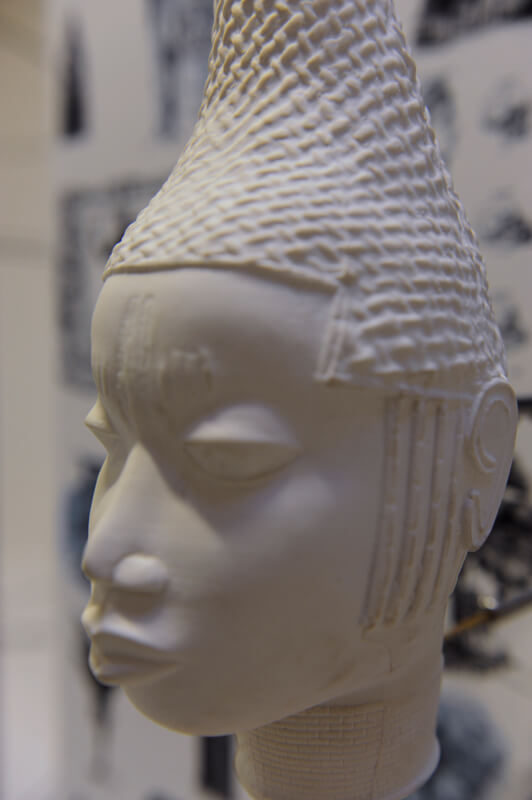

RRR (Rapid Response Restitution)

Sculpture Installation

2022

Inspired by the hundreds of thousands of sculptures plundered for centuries and lying in our museums an iconic piece, such as an Iyoba -or queen mother- is reproduced in the finest white porcelain. The two pieces are shown suspended "flying" over a circular backlit structure made of birch wood, on a wallpaper background.

In the background a wallpaper with Toile de Jouy style motifs introduces another layer of reading, transforming the characteristic drawing that usually appears in these motifs into a representation of the documented massacres of the plunderers, more specifically the so-called Benin Massacre, and other historical stereotypical representations of the African continent.

The Queen Idia depicted here was considered the driving force behind her son's successful military campaigns against neighboring kingdoms. According to the history of the Kingdom of Benin, after the death of Queen Idia, Oba (king) Esigie commissioned the casting of heads with dedications to the queen to be placed before the altars of the queen mother's palace.

The Benin Bronzes are a group of more than a thousand plaques and metal sculptures created from the 13th century that decorated the Royal Palace of the Kingdom of Benin. They were violently looted during the colonization period during a punitive expedition of the English army in 1897 in the so-called Benin Massacre.

The total number of objects looted amounted to 10,000 bronzes, ivories and other objects. Taken to the British Museum in London, they were distributed from there to various European and American museums.

The majority, hundreds of them, hibernate in their basements, a sign of intolerable cultural greed.

For the installation of the piece in the room, 2 reproductions would be placed in different versions: one white and the another with the face with the drawing of the wallpaper superimposed on the skin.

On the wallpaper wall you will also see a framed photographs of the project in various sizes

In the background a wallpaper with Toile de Jouy style motifs introduces another layer of reading, transforming the characteristic drawing that usually appears in these motifs into a representation of the documented massacres of the plunderers, more specifically the so-called Benin Massacre, and other historical stereotypical representations of the African continent.

The Queen Idia depicted here was considered the driving force behind her son's successful military campaigns against neighboring kingdoms. According to the history of the Kingdom of Benin, after the death of Queen Idia, Oba (king) Esigie commissioned the casting of heads with dedications to the queen to be placed before the altars of the queen mother's palace.

The Benin Bronzes are a group of more than a thousand plaques and metal sculptures created from the 13th century that decorated the Royal Palace of the Kingdom of Benin. They were violently looted during the colonization period during a punitive expedition of the English army in 1897 in the so-called Benin Massacre.

The total number of objects looted amounted to 10,000 bronzes, ivories and other objects. Taken to the British Museum in London, they were distributed from there to various European and American museums.

The majority, hundreds of them, hibernate in their basements, a sign of intolerable cultural greed.

For the installation of the piece in the room, 2 reproductions would be placed in different versions: one white and the another with the face with the drawing of the wallpaper superimposed on the skin.

On the wallpaper wall you will also see a framed photographs of the project in various sizes

Instalación de 2 reproducciones en porcelana de la cabeza de una Iyoba (Reina Madre) del Reino de Benín, parte de los famosos Bronces de Benín, suspendida sobre una base circular, horizontal y retroiluminada, sobre un fondo de wallpaper.

Un papel mural que hace un guiño a los famosos wallpaper Toile de Jouy recubre las paredes de la instalación con imágenes y grabados representando motivos de tesoros expoliados durante expediciones punitivas, saqueos, violencias, representaciones racistas e imaginario construido de África.

La reina Idia aquí reproducida fue considerada la fuerza motriz de las exitosas campañas militares de su hijo contra los reinos vecinos. Según la historia del Reino de Benín, tras la muerte de la reina Idia, Oba (rey) Esigie encargó la fundición de cabezas con dedicatorias a la reina para colocarlas delante de los altares del palacio de la reina madre.

Los Bronces de Benín son un grupo de más de mil placas y esculturas de metal que decoraban el Palacio Real del reino de Benín creados a partir del siglo XIII y que fueron saqueados violentamente durante el periodo de colonización durante en una expedición punitiva del ejército inglés en 1897 en la llamada Masacre de Benín.

La cifra total de objetos saqueados ascendía a 10.000 bronces, marfiles y otros objetos. Llevadas al British Museum de Londres, se repartieron desde ahí por diversos museos europeos y de Estados Unidos.

La mayoría, cientos de ellos, hibernan en los sótanos de estos, muestra de una intolerable avaricia cultural.

Para su instalación en sala se colocarían 2 reproducciones en distintas versiones: una blanca y otra con la cara con el dibujo del papel de la pared superpuesto en la piel.

En la pared de wallpaper también se verán fotografía enmarcada del proyecto de diversos tamaños

Un papel mural que hace un guiño a los famosos wallpaper Toile de Jouy recubre las paredes de la instalación con imágenes y grabados representando motivos de tesoros expoliados durante expediciones punitivas, saqueos, violencias, representaciones racistas e imaginario construido de África.

La reina Idia aquí reproducida fue considerada la fuerza motriz de las exitosas campañas militares de su hijo contra los reinos vecinos. Según la historia del Reino de Benín, tras la muerte de la reina Idia, Oba (rey) Esigie encargó la fundición de cabezas con dedicatorias a la reina para colocarlas delante de los altares del palacio de la reina madre.

Los Bronces de Benín son un grupo de más de mil placas y esculturas de metal que decoraban el Palacio Real del reino de Benín creados a partir del siglo XIII y que fueron saqueados violentamente durante el periodo de colonización durante en una expedición punitiva del ejército inglés en 1897 en la llamada Masacre de Benín.

La cifra total de objetos saqueados ascendía a 10.000 bronces, marfiles y otros objetos. Llevadas al British Museum de Londres, se repartieron desde ahí por diversos museos europeos y de Estados Unidos.

La mayoría, cientos de ellos, hibernan en los sótanos de estos, muestra de una intolerable avaricia cultural.

Para su instalación en sala se colocarían 2 reproducciones en distintas versiones: una blanca y otra con la cara con el dibujo del papel de la pared superpuesto en la piel.

En la pared de wallpaper también se verán fotografía enmarcada del proyecto de diversos tamaños

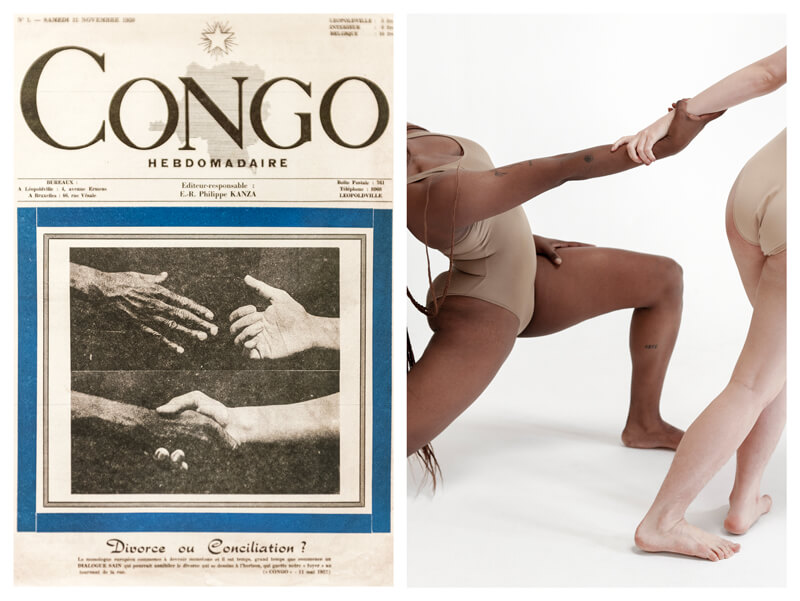

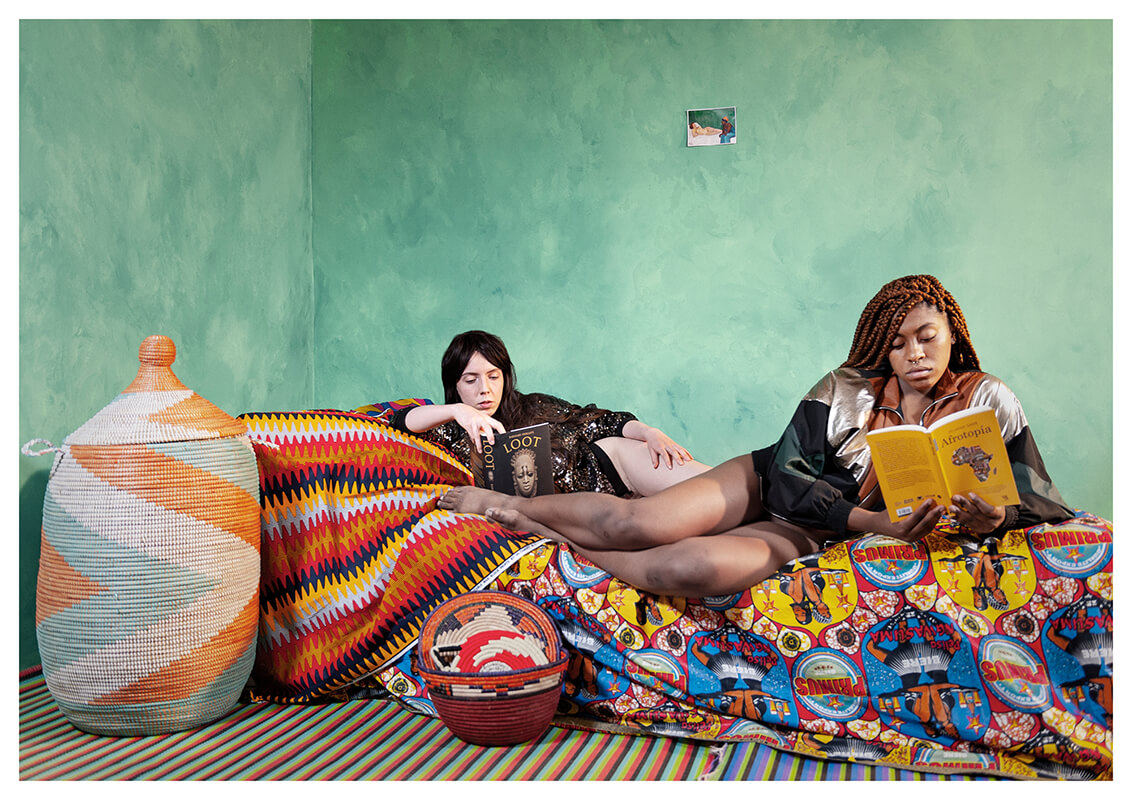

La Blanche et la Noire

Photography

2022

Reflection from the painting La Blanche et la Noire (1913) by Felix Valloton. As a tableau vivant, with free interpretation and evolving towards a contemporary reflection.

Inspired by Manet's Olympia and Ingres' Odalisque à l'esclave, it presents the Sapphic loves between a sylph and a black woman. Unlike his predecessors, Vallotton gets rid of all exotic references., confronting a white female nude in a passive position in contrast to the black woman who looks at her while smoking a cigarette in an almost masculine attitude, refraining from any attempt at seduction.

In the recreation and later versions, both the white model and the black woman appear lying or standing, naked or semi-dressed, crowned and covering her face with an allegorical headdress inspired by the tradition of the "crowns" of the Obba (queen or goddess of fertility) of the Yoruba ethnic group/religion, in which different animals and human figures are represented.

To end up in a more contemporary reflection, a two-voice dialogue emerges between the two women reflecting on gender, race and colonialism while they read books such as "Afrotopia" by Senegalese thinker Felwine Sarr (co-creator with historian Benedict Savoy of the report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron on the issue of looted objects in French museums, especially the Quai Branly Museum) or "Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes" by Barnaby Phillips.

The responsibility for the representation of black women in European painting, lthe position of the white woman and the black woman in Victorian times (when colonialism in Africa reinforced the most oppressive imaginary), the stereotyping, exoticization and the cultural appropriations.…

Key concepts of world wide feminist thought -home, sisterhood, experience, community- mark the way towards a borderless feminism fully engaged with the realities of a transnational world.

This series is made up of 6 large-format photographs.

Inspired by Manet's Olympia and Ingres' Odalisque à l'esclave, it presents the Sapphic loves between a sylph and a black woman. Unlike his predecessors, Vallotton gets rid of all exotic references., confronting a white female nude in a passive position in contrast to the black woman who looks at her while smoking a cigarette in an almost masculine attitude, refraining from any attempt at seduction.

In the recreation and later versions, both the white model and the black woman appear lying or standing, naked or semi-dressed, crowned and covering her face with an allegorical headdress inspired by the tradition of the "crowns" of the Obba (queen or goddess of fertility) of the Yoruba ethnic group/religion, in which different animals and human figures are represented.

To end up in a more contemporary reflection, a two-voice dialogue emerges between the two women reflecting on gender, race and colonialism while they read books such as "Afrotopia" by Senegalese thinker Felwine Sarr (co-creator with historian Benedict Savoy of the report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron on the issue of looted objects in French museums, especially the Quai Branly Museum) or "Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes" by Barnaby Phillips.

The responsibility for the representation of black women in European painting, lthe position of the white woman and the black woman in Victorian times (when colonialism in Africa reinforced the most oppressive imaginary), the stereotyping, exoticization and the cultural appropriations.…

Key concepts of world wide feminist thought -home, sisterhood, experience, community- mark the way towards a borderless feminism fully engaged with the realities of a transnational world.

This series is made up of 6 large-format photographs.

Fotografías realizadas a partir del cuadro La Blanche et la Noire (1913) de Felix Valloton a modo de tableau vivant, con interpretación libre y evolucionando hacia una reflexión contemporánea.

Inspirado en la Olympia de Manet y la Odalisque à l'esclave de Ingres, representa el amor sáfico entre una sílfide y una mujer negra; pero a diferencia de sus predecesores, Vallotton prescinde de toda referencia exótica, enfrentando un desnudo femenino blanco en posición pasiva en contraste con la mujer negra que la mira mientras fuma un cigarrillo en actitud casi masculina, absteniéndose de toda tentativa de seducción.

En la recreación y posteriores versiones, aparecen tanto la modelo blanca como la mujer negra recostadas o de pie, desnudas o semi vestidas, coronadas por tocados alegóricos inspirados en la tradición de las “coronas” de las Obba (reina o diosa de la fertilidad) de la religión Yoruba, en el que se representan distintos animales y figuras humanas.

En una última versión retrofuturista, surge entre ellas un diálogo a dos voces en torno al género, la raza y el colonialismo mientras leen "Afrotopía", del pensador senegalés Felwine Sarr (cocreador junto a la historiadora Benedict Savoy del informe encargado por el presidente francés Emmanuel Macron sobre la cuestión de los objetos saqueados en los museos franceses, especialmente en el Museo Quai Branly) y ‘Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes’ , de Barnaby Phillips.

La responsabilidad de la representación de la mujer negra en la pintura europea, la posición de la mujer blanca y la mujer negra en época victoriana(cuando el colonialismo en África reforzaba el imaginario más opresor), estereotipación, exotización y el apropicionismo cultural,… Conceptos clave del pensamiento feminista -hogar, hermandad, experiencia, comunidad- marcan el camino hacia un feminismo sin fronteras.

La serie está formada por 6 fotografías de gran tamaño.

Inspirado en la Olympia de Manet y la Odalisque à l'esclave de Ingres, representa el amor sáfico entre una sílfide y una mujer negra; pero a diferencia de sus predecesores, Vallotton prescinde de toda referencia exótica, enfrentando un desnudo femenino blanco en posición pasiva en contraste con la mujer negra que la mira mientras fuma un cigarrillo en actitud casi masculina, absteniéndose de toda tentativa de seducción.

En la recreación y posteriores versiones, aparecen tanto la modelo blanca como la mujer negra recostadas o de pie, desnudas o semi vestidas, coronadas por tocados alegóricos inspirados en la tradición de las “coronas” de las Obba (reina o diosa de la fertilidad) de la religión Yoruba, en el que se representan distintos animales y figuras humanas.

En una última versión retrofuturista, surge entre ellas un diálogo a dos voces en torno al género, la raza y el colonialismo mientras leen "Afrotopía", del pensador senegalés Felwine Sarr (cocreador junto a la historiadora Benedict Savoy del informe encargado por el presidente francés Emmanuel Macron sobre la cuestión de los objetos saqueados en los museos franceses, especialmente en el Museo Quai Branly) y ‘Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes’ , de Barnaby Phillips.

La responsabilidad de la representación de la mujer negra en la pintura europea, la posición de la mujer blanca y la mujer negra en época victoriana(cuando el colonialismo en África reforzaba el imaginario más opresor), estereotipación, exotización y el apropicionismo cultural,… Conceptos clave del pensamiento feminista -hogar, hermandad, experiencia, comunidad- marcan el camino hacia un feminismo sin fronteras.

La serie está formada por 6 fotografías de gran tamaño.